Mapping the Transmission of Infectious Diseases Using Next-Generation Sequencing

In this interview, Dr. Judd F. Hultquist shares how his early discoveries in corn flowers led to a passion for infectious disease research and a desire to understand the mechanism behind viral transmission in a population. Judd also shares his insights on challenges and opportunities during a pandemic and how his lab uses next-generation sequencing to analyze and understand the spread of COVID-19.

Published December 16, 2020

The following transcribed interview has been lightly edited for clarity and brevity.

Judd’s Story: How corn flowers, the fight for equality, and viral infections shaped a scientist

What inspired you to become a scientist?

It’s one of those tricky questions. My first exposure to research was plant biology. Growing up, one of my favorite places was our family cabin up in the pine woods of northern Wisconsin, so I found it natural to start my undergraduate research in plant biology. I was researching corn—Wisconsin has a lot of corn—and my first discovery was of a microRNA that regulates differentiation of the male flowers or tassels of corn. It’s unlike anything I’ve ever felt before and it remains, to this day, my favorite high. That high of discovery. Realizing when you have found something—and scientifically proven it to yourself—realizing that you're the first person in the world to have known that one particular fact, no matter how small it is... it is an incredible experience. So I think that experience, more than anything else, really hooked me in the scientific endeavour.

Realizing when you have found something—and scientifically proven it to yourself—realizing that you're the first person in the world to have known that one particular fact, no matter how small it is...it is an incredible experience.

Dr. Judd F. Hultquist

In Sickness and in Health: The Fight for Equality

What took you from the high of corn research to the study of infectious diseases like Ebola, HIV, and COVID-19?

Well, I wanted to pursue my PhD and determining what to study in graduate school was a difficult choice. As a gay man, choosing to work with infectious diseases like HIV was important as a way to give back to my community. My partner and I met when we were both in undergrad and, at that time, it was in vogue in the United States for conservative lawmakers to pass anti-gay marriage amendments forbidding the union between same-sex couples. My partner and I actually had met while volunteering at an LGBTQ youth organization in Milwaukee after protesting against the anti-marriage amendments. So it was while we were fighting for our own civil liberties that I was trying to choose what I wanted to study as a scientist, and studying HIV was one way where I felt like I could give back to this really supportive community that had given me so much.

The more you learn about infectious disease in general, the more you find that it truly is a history of opportunistic infection and inequalities. The people who have the fewest resources to protect themselves from a disease, be it HIV, flu, or now COVID-19, they are the ones that end up suffering the most. Both in terms of raw numbers of who gets infected and also in terms of consequences. It might not mean that much if I end up sitting out of work for a week with the flu, but for somebody who absolutely needs that job to support themselves and support their family, a week’s absence is huge. And these risks only increase with the severity of the disease.

The more you learn about infectious disease in general, the more you find that it truly is a history of opportunistic infection and inequalities. The people who have the fewest resources to protect themselves from a disease, be it HIV, flu, or now COVID-19, they are the ones that end up suffering the most.

Dr. Judd F. Hultquist

The Global COVID-19 Pandemic: Challenges and Opportunities

Why do you think so many in the scientific community were surprised when COVID-19 really took hold?

There are all kinds of infectious diseases that jump from animals into humans, so-called zoonotic infectious diseases. People tend to think of them as these rare events, but they are actually happening all the time. HIV is a prominent example, having jumped from monkeys into humans, but we have many others such as SARS, MERS, and other coronaviruses. We’ve had several types of influenza virus jump into the human population, such as swine flu and bird flu, as well as an assortment of other diseases, such as Ebola virus, which has been causing sporadic outbreaks in Africa. So the idea of a zoonotic infection taking hold in the population isn’t something that’s new. I think what really caught us all off guard was how rapidly and silently this particular one was able to spread. All of these other infectious diseases, either they spread fairly slowly, can be easily tracked by symptoms, or do not result in as much severe disease. So, for example, Ebola is very severe but it doesn’t spread very easily or very fast. On the other hand, the flu—while also no picnic—is usually not as severe as Ebola virus infection or COVID-19. COVID-19 really borders that line between fast transmission and severity where it becomes scary. Adding on the ability of SARS-CoV-2 to spread asymptomatically, that’s really when a virus becomes dangerous.

COVID-19 really borders that line between fast transmission and severity where it becomes scary. Adding on the ability of SARS-CoV-2 to spread asymptomatically, that’s really when a virus becomes dangerous.

Dr. Judd F. Hultquist

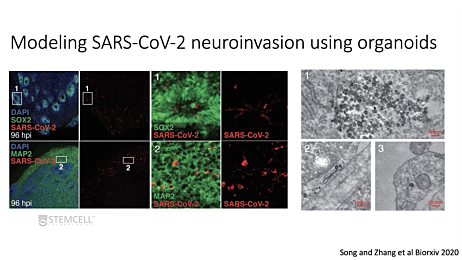

How are you and your team currently studying Coronavirus?

My lab specializes in high-throughput ‘OMICS’-approaches. What these approaches are designed to do is to gather as much information about a given system at one time as possible, and then we use computational approaches to understand what all the data means. To help in the battle against coronavirus, we are trying to understand if SARS-CoV-2 is changing over time in the population and if those viral changes have any impact on severity or treatment outcome. This required us to access large amounts of clinical data, and to pair that data with viral sequencing. To do that, we’ve been working in partnership with a local hospital to get samples and then use next-generation sequencing approaches to analyze the virus sequences in each of our patients.

You recently published a paper in EBioMedicine1 using these approaches. What were your findings in that paper and what is your next step?

Our initial findings were based on sequences of viruses in Chicago. The questions we asked were “Can we identify where these viruses came from?” and “Can we identify how many different types of virus are circulating in the Chicago area?” Once we identify how many types of virus there are, then we can look to see whether or not there are differences in severity, patient outcomes, and the ability to treat patients with various antivirals. That's what this initial report was really focused on.

Now that we have an idea of what viruses are circulating in the Chicago area we can start asking “What happens to these over time?” Part of what our research is now morphing into is tracking these infections in the population and in individuals and seeing how the virus is adapting over time.

Our ultimate goal is to sequence roughly 1000 different viral genomes from 1000 distinct patients, because with that number we can really begin to ask more granular questions than we were able to ask with this first subset.

SARS-CoV-2 Viral Diversity: Causes, Consequences, and Opportunities

The rapid spread of SARS-CoV-2 has been accompanied by the emergence of distinct viral clades, though their clinical significance remains unclear. In this webinar, Dr. Judd F. Hultquist discusses his recent data on how differences in virus genotype impact viral load and influence viral transmission and spread.

Watch Now >There are reports of a potential link between COVID-19 and systemic inflammation in children. Is this something that the scientific community is taking seriously or is this media hype?

It’s both. Obviously, whenever there are unexpected complications, especially in children, it’s something that clinicians and the scientific community take very seriously. It’s the last thing we want to see but, that being said, it’s still an exception as opposed to a rule. In fact, many children don’t present with symptoms at all, and so trying to understand these differences in clinical outcome is a major unknown that a lot of different groups, including our own, are beginning to try to dissect. An estimated 80% of infections have no or only mild symptoms, whereas a large number of cases require hospitalization. Why is that? It can’t all be explained based on viral diversity, there has to be some difference within ourselves that can account for this, and that applies both to adults and children. So trying to identify what’s the predictor of disease severity in adults and in kids is really important.

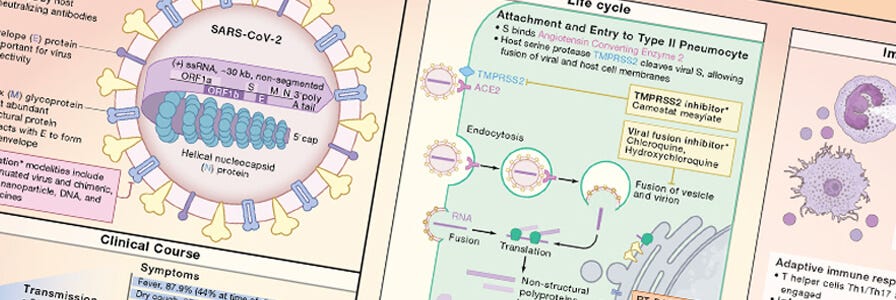

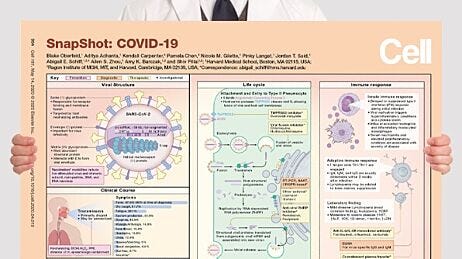

COVID-19 Wallchart

Download this free wallchart to get an overview of the innate and adaptive immune response to SARS-CoV-2 and the development of investigational therapies and vaccines for COVID-19.

Request a Copy >What do you think are the main scientific challenges that COVID-19 researchers are facing?

I have been having this kind of discussion with my students quite a bit, because science typically moves at a certain, fairly slow and regular pace, and that pace is dictated by the fact that we want to be absolutely certain that everything that we publish, everything we do, is 100% fact. Now we are faced with this difficult circumstance—where the need to identify new information and test new hypotheses is so critical to our ability to combat this virus right now—that we have to speed up the science, but that requires us to treat new information very carefully. One thing we are beginning to see in the scientific community that has become really popular, especially with COVID-19, are pre-peer-review publications. I’m sure you’ve seen a lot of articles come out that make news headlines in medRxiv or bioRxiv, which are these repositories of manuscripts that people are working on that have not yet been evaluated by the broader scientific community. It is a really important way of sharing information, but it always comes with this caveat: How much can you trust what’s on there? Peer review is the backbone of scientific integrity and science takes a long time. It just does. We want to move as fast as we can with as much confidence as we can, but that means we have to be very cautious consumers of information.

How has COVID impacted your research practices in the lab? Has it forced your lab to be more efficient?

Yes, I think there are definitely some places where it’s more efficient. I think it’s also benefited from the fact that everybody who is working in the lab now is dedicated to finding some solution to this horrific problem. Coming into the lab and seeing all these researchers giving it their all and putting their lives on the line in order to get this research done, is really inspiring. I think that’s another really bright-line aspect. You get to work as part of this dedicated community. It’s inspirational.

Advice for Future Graduate Students

What is your advice to new graduate students entering academia?

My recommendation is to be nice to yourself. Be your own best friend. You have to advocate for yourself. You have to be generous with yourself and you have to be forgiving of yourself. I’ve seen scientists be successful in so many different ways, but everybody that I’ve seen become a successful scientist has been willing to treat themselves with the respect they would treat anyone else. It’s really easy when you come in the lab and your experiments are all failing and everything takes forever to really kind of get down on yourself or to try to measure yourself to other people or other labs, but you have to be kind to yourself. There are so many ways to contribute to the scientific enterprise; you have to identify your strength and then move that forward.

It’s really easy when you come in the lab and your experiments are all failing and everything takes forever to really kind of get down on yourself or to try to measure yourself to other people or other labs, but you have to be kind to yourself. There are so many ways to contribute to the scientific enterprise; you have to identify your strength and then move that forward.

Dr. Judd F. Hultquist

Nine Tips for Thriving in Academic Research

From graduate students to seasoned principal investigators, we asked scientists for advice for the next generation of scientists. See what they had to say.

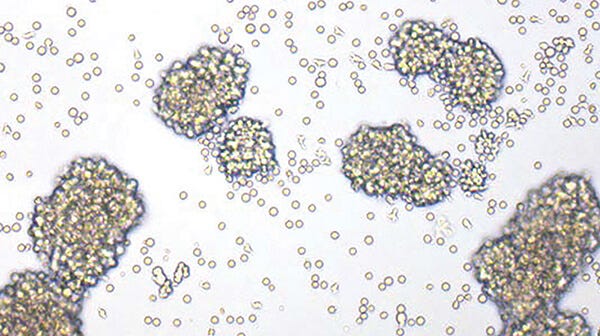

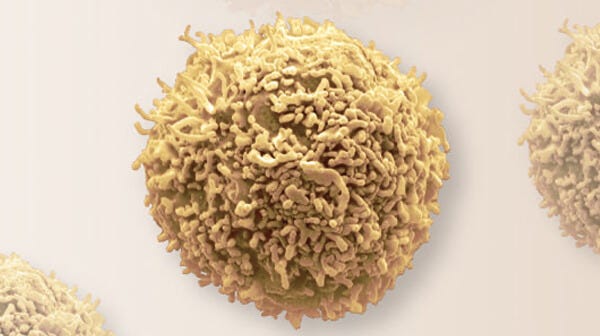

Read Now >Cell Isolation and Gene Editing

Are you currently using any STEMCELL products?

I use STEMCELL’s various positive and negative selection kits quite frequently, particularly for isolation of CD4+ cells, resting memory cells, and also CD3+ cells. In our HIV work, we do a lot of functional genomics work where we isolate CD4+ T cells out of blood and then we use CRISPR-Cas9 ribonucleoproteins to edit their genomes. Then we take those T cells that have been modified and challenge them with HIV, and monitor the HIV infection in these cultures over time to see how different genetic alterations change the replication profile. That’s what we need the STEMCELL kits for, we need to isolate those cells out. I love STEMCELL stuff because it works. As a grad student I used columns, and I just, I hated them so much. My current students are spoiled now with these products.

View more Immunology Profiles. Think you or someone you know should be featured in a profile? Let us know!

Developing Vaccines and Therapies Against Viral Diseases

Vaccine Development

Learn about tools and assays for developing vaccines, including products for sourcing and isolating immune cells, assessing vaccine candidates, and developing production lines for recombinant vaccines.

Learn More >Therapeutic Development

Explore technologies, applications, and research tools for developing and assessing therapeutics to combat viral diseases such as COVID-19.

Learn More >View more tools and resources for COVID-19 Research.

Products for Your Infectious Disease Research

Human Primary Cells

Access fresh or cryopreserved cells, including mononuclear cells (MNCs), purified immune cells, or stem cells isolated from blood.

Resources for Studying Coronavirus Infections

References

- Lorenzo-Redondo, R et al. (2020) A clade of SARS-CoV-2 viruses associated with lower viral loads in patient upper airways, EBioMedicine 62, 103112. Epub ahead of print. DOI: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.103112.

Request Pricing

Thank you for your interest in this product. Please provide us with your contact information and your local representative will contact you with a customized quote. Where appropriate, they can also assist you with a(n):

Estimated delivery time for your area

Product sample or exclusive offer

In-lab demonstration