The 7 Habits of Highly Effective Presenters

Sharing your work with the global scientific community is one of the most important duties you have as a scientist. Feeling comfortable with public speaking and presenting is a vital skill for scientists, regardless of whether you are in a lab meeting with your colleagues or standing in front of hundreds of your peers at a global conference.

However, an estimated 20% of the population1 suffers from a genuine fear of public speaking, and many more of us feel uncomfortable at the prospect. Fear of public speaking can manifest physically—as nervous trembling, nausea, sweating, dizziness—or psychologically, with brain fog, fatigue, negative thoughts, or other symptoms.

As scientists, simply avoiding presentations isn't a sustainable solution. We're taking a look at how, with some preparation and practice, you can feel more comfortable about presenting your research. With time, you may even grow to enjoy it!

Be Prepared

It may seem like a no-brainer, but being well prepared for your presentation can help to relieve some of the anxiety that comes with public speaking.

To start, break down the task of preparing for your presentation by creating a list of concrete, achievable goals. These could include:

- Making your slides

- Preparing talking points

- Holding practice sessions

Ticking each goal off your list as you complete it can help boost your confidence and reassure you that you are fully prepared for the presentation.

A well-prepared slideshow and a cheat sheet of notes can help to prompt you if you stumble or become flustered during your presentation. Rather than writing out exactly what you want to say, try using prompts, such as words or short bullet-points, so that you don't come across as over-rehearsed, or panic if you lose your place.

You may even find that you don't end up using these notes during your presentation, but they will be a comfort to have, just in case.

When you practice your presentation, it can be useful to have a friendly but critical audience: ask your peers or fellow lab members to come up with questions about your research. This can help you to anticipate audience questions and prepare answers in advance.

Finally, it can help to check out the venue before your presentation so you are not walking into the unknown—drop by the evening before or the morning of the presentation to see what kind of room you will be speaking in.

Check out our top 10 tips for attending conferences >

Let Your Research Speak for Itself

Your research, when properly presented, will do most of the talking for you. Use it to tell a story with a beginning, a middle, and an end.

The introduction section of your presentation lays out the purpose or objective of the presentation: Why are you giving this presentation? What point(s) are you trying to get across? Grab the attention of the audience by presenting your hypothesis and explain why it is important to the field.

When writing your introduction, think about your audience and pitch it a level appropriate to their existing knowledge.

In the body of your presentation, provide the evidence to support your hypothesis with one clear point per slide. Pick the data you present carefully, making sure that you present it with a logical flow that supports your story. Your data should be cleanly presented with clear titles and figure legends, so your audience can quickly and easily grasp what they show and evaluate for themselves.

Be wary of presenting slides filled with words. Slides are an accompaniment to your presentation and should visually represent what you are speaking about. Use simple figures, graphs, and short, succinct sentences that you can expand upon as you explain your research.

Finally, have a summary at the end of your presentation to link back to your initial hypothesis. Don’t forget to include a slide acknowledging your collaborators and support before you open the floor to questions from the audience.

Engage Your Audience

To fully engage the audience and to make the most of your presentation, use your slides effectively.

Often, scientists will present a great deal of fascinating but complex data without fully explaining it. Make sure your audience understands your data by giving a brief overview of what is on the slide: slowly and clearly walk through each figure to explain labels and axes, key details, and why this data is important to your hypothesis.

When you are presenting in person, there is a balance to strike between effectively using your slides and paying attention to your audience. It can be tempting to keep your eyes fixed on your notes or to focus on the slide on-screen with your back to the audience. However, making eye contact with members of the audience shows that you are interested in their reaction and are confident in what you are discussing.

It is likely that some people in the audience will not be engaged. They may show this with their body language (looking at their cell phone, folded arms). Try not to focus on these people; instead concentrate only on the people who are interested in what you're talking about.

Manage Your Anxiety

Managing your anxiety on the day of your presentation is a key part of ensuring it doesn’t overcome you. Feeling nervous before a presentation is normal and to be expected—even if you don’t feel nervous in the days, weeks or hours coming up to the presentation, the 30 minutes beforehand may be filled with anxiety.

Deep breathing and relaxation techniques can help to relieve both physical and mental signs of anxiety. Learn to recognize self-critical thoughts and dismiss or replace them with more realistic and positive thoughts (instead of “they’ll think I don’t know what I’m talking about”, think of all the work you have put into your research and presentation). No matter how new you are to the field, you are the expert on your work and likely know it better than anyone else in the room.

Similarly, if you are concerned about questions from the audience, it can help a lot if you think of the questions as opportunities to further the discussion about your research, rather than a grilling—you don’t need to know all the answers.

Act Confident—Even if You’re Not

It may not be easy to feel confident when you feel the weight of a thousand (or so it seems) eyes on you, but acting confident can make a big difference to the quality of your presentation.

If you're not feeling particularly confident, you can trick yourself—and those watching—by practicing confident body language, otherwise known as power posing.

Though the debate on the 'power posing effect' is ongoing2, there are studies which suggest that practicing expansive body language3, such as standing with your hands on your hips (the 'wonder woman pose') or with your arms outspread over your head (the 'victory pose'), during or immediately prior to a presentation can instill a sense of confidence both in yourself and your audience. Even if the power posing effect isn't wholly accepted by the scientific community, it can still help take your mind off of the impending presentation.

When you stand in front of your audience, take your time to begin speaking. This can give the appearance that you are a confident speaker as well as giving you the opportunity to ground yourself before you begin your presentation. If you worry about getting flustered, taking a sip of water can be a great excuse to take a moment to gather yourself.

Speak slowly and distinctly throughout the presentation to help hide your nerves, and to give your audience the time they may need to understand more complex topics. Be mindful of inserting pauses when speaking, and speak more slowly than you would in everyday conversation.

Practice, Practice, Practice

In time, you may grow to love public speaking—or you may not. Either way, the more you practice presenting in front of people, the easier it will become.

Practice in front of the mirror, practice in front of your friends, practice in front of your lab or roommates. Rehearse your presentation at least three times, and try to do so in front of different groups of people. Ask for feedback on your presentation skills as well as the presentation itself: Do you need to speak more slowly? More loudly? More clearly?

Though it may be tempting to avoid presenting unless you absolutely have to, volunteering for speaking opportunities can result in valuable experiences to practice and to help reduce your presentation anxiety.

Remember We’ve All Been There

Many of those in the audience will have experienced the exact same feeling of presentation anxiety. They will have an understanding of the nerve it takes to present your research.

Before you face them, take a moment to remind yourself of the following:

- The audience is there to listen to you: they’re interested in what you have to say.

- This is the first time they have heard this presentation: they’re not going to notice that the joke you had planned for halfway through your second slide never came, or that you fumbled over the protein name you’ve said a million times perfectly before.

- Nobody is perfect—and your audience doesn’t expect you to be, either!

And, most importantly, remember that we’re all in this together, with the same aim of sharing our research and driving the field forward.

Looking for More Tips on Presenting?

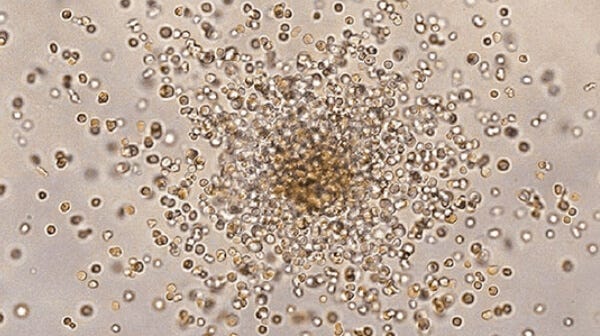

Warm yourself up to the thought of presenting by watching these webinars featuring key opinion leaders in the hematopoietic field. Ask yourself, are these speakers good at presenting? Why, or why not? Make a list of do's and don'ts for your own presentation.

Hematopoietic Research Resource Center

Tips and Tricks for Working Smart in the Lab

Immunology Research Resource Center

References

- Furmark T et al. (1999) Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 34(8): 416–24.

- Biello D. (2017) IdeasTedCom. Retrieved from https://ideas.ted.com/inside-the-debate-about-power-posing-a-q-a-with-amy-cuddy/

- Carney DR et al. (2010) Psychol Sci 21(10): 1363–8.